FEB 28, 2020

When my sons were struggling with reading, I turned to the internet for answers. I searched Struggling Readers. Sight Words. Dyslexia. Phonics. Children who cry when they read. Why is English so hard? I read blogs. I read articles in educational journals. I ordered books, lots of books. Never once did I consider that there was a science to how people learn to read.

By the time they were in second grade and still not reading, I felt discouraged. At night, I would worry about their futures.

Then I found a book that described the Orton phonograms and spelling rules; I couldn't put it down!

I was captivated by facts such as S says TWO sounds, /s/ and /z/. Instantly, I understood why my sons kept misreading his as hiss and is as iss. They had only been taught that S says /s/, as in sand. When they came across a word where it said /z/ and they misread it, they were told, “That is a sight word.” Yet, S says /z/ in tens of thousands of words. It is not an exception!

When I read that there were additional reasons for a silent final E, I jumped up off the couch and ran upstairs and announced to everyone who was home, “Did you know? There is more than one reason for a silent final E! English words do not end in V, therefore add an E! This explains words like have and give. The C says /s/ because of the E! This is why we have a silent final E in lace and it doesn’t say lake. The G says /j/ because of the E! This explains large and hinge!”

Suddenly I had hope. Maybe the problem wasn’t that there was something wrong with my sons. Maybe the problem was what they had been taught.

Until this point, the boys had been struggling to learn to read with a balanced literacy approach. They were surrounded by books. We had read to them daily since birth. They loved looking at books and listening to books, including chapter books. We played rhyming games and other word games. They learned some phonics. They knew the letter names and the basic sounds, such as A says /ă/ as in ăpple and /ā/ as in cāpe, and C says /k/ as in cat. They learned SH says /sh/ as in ship, and igh says /ī/ as in night. They practiced reading words that follow the rule the silent E makes the vowel say its name, such as game. And to cover all the words that didn’t follow the phonics rules, they were taught sight words. We drilled the sight words so that they would have the tools to read real books.

But it didn’t work. They never progressed beyond reading phonetically controlled readers that had strange sentence structures and boring stories.

When they tried to read real books or even Level 1 or 2 Readers, it felt like they were misreading every third or fourth word. I was constantly saying, “That is an exception.” Or “That is a sight word.” The boys became discouraged. They dreaded reading. They would wiggle off the sofa. And they would cry.

After reading about the phonograms and spelling rules, I realized they didn’t have all the tools to read all the words.

I stopped torture reading with the boys and went back to reading books aloud to them. At a different time of the day, we filled in their gaps in phonics knowledge. The first day, we went through all the phonograms in the book and discovered which ones we knew all the sounds to.

Each day we learned two or three new phonograms, or added sounds to the ones we knew, or learned new spelling rules. I would write words that used the new phonogram or rule on a whiteboard, and they would practice reading them. We made up silly games to make it fun. Then we practiced writing words that used the new concept. I would say a word, and they would sound it out. They would write it. Then they sounded it out for me.

Within three months, something amazing happened: they began reading chapter books. They read The Chronicles of Narnia, Warrior, and Redwall. They loved reading! And they skipped all the level two and three readers. At the time I wondered, how was that possible? It is explained by the neuroscience of reading.

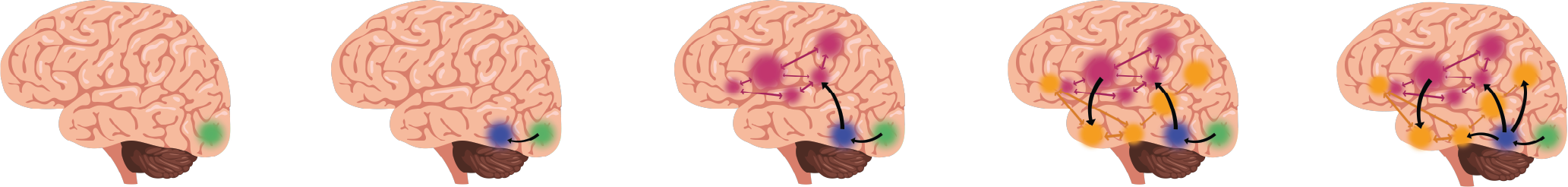

Strong readers use the same part of their brain to read as they use to listen. When we listen and comprehend, our brain recognizes the sounds and then connects these sounds to another area that stores the meaning. Strong readers have trained a special part of their brain called the letterbox. The letterbox recognizes that a letter or group of letters represents a sound. It then passes the signal to the same area of the brain that recognizes sounds, and the pathway continues to where the meaning is stored(1).

When students accurately learn how the sounds in a language are represented, their brains are able to use the same pathways that are used for listening to read. This is also explained by the Simple View of Reading(2), which states that a student’s reading comprehension is equal to their ability to listen and comprehend TIMES their decoding skills.

Because my sons could listen to a chapter book and comprehend it, as soon as they learned accurate decoding skills they could apply that knowledge to read and comprehend at the same level.

This is the science of reading at work. It is powerful! And it explains the transformation that struggling readers, like my sons, experience when they learn how to apply accurate phonics with all of the phonogram sounds and spelling rules to decode words.

______________________

(1) Dehaene, Dr. Stanislas. “Lecture by Dr. Stanislas Dehaene on ‘Reading the Brain.’” April 30, 2013. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=MSy685vNqYk.

(2) Farrell, Linda, Marcia Davidson, Michael Hunter, and Tina Osenga. “The Simple View of Reading.” Accessed April 9, 2021. https://www.cdl.org/the-simple-view-of-reading/.